Overload Resolution and Covariance

As of C# 4.0, generics support covariance and contravariance. I won’t talke about contravariance in the post, however.

To sum it up quickly, covariance enables implicit conversion of a generic collection of type T to the same generic collection of a type that derives from T. In short:

IEnumerable<Object> list = new List<String>().AsEnumerable();

This means that as of now, any method that accepts something like IEnumerable<Object> can accept an IEnumerable<String> as well. This changes the overload resolution mechanism:

class A { } class B : A { } class T { internal void Foo(IEnumerable<B> sequence) { Console.WriteLine("In T.Foo.B"); } } class U : T { internal void Foo(IEnumerable<A> sequence) { Console.WriteLine("In U.Foo.A"); } }

In the following code, how does the method resolution changes?

U u = new U(); var l = new List<A>(); var m = new List<B>(); u.Foo(l); u.Foo(m);

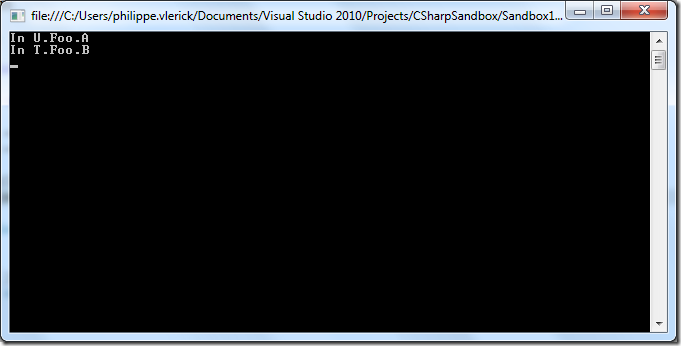

If ran in Visual Studio as a .NET 3.5 application, here is the result:

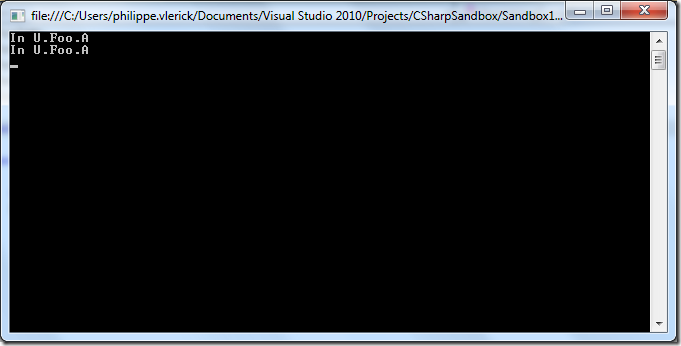

If ran in Visual Studio as a .NET 4.0 application, here is the result:

Prior to C# 4.0, U.Foo was not a candidate for a call using a generic collection of B. However, with covariance, it is, hence the different result. So, this is no breaking change, but the behavior of an application might be affected.

blog comments powered by Disqus